Google has abandoned its effort to come up with better flat mirrors and power plant designs for producing electricity from the sun’s heat, but it is releasing its research results so that others could perhaps use it to create commercially viable solutions.

It’s interesting to see what Google thought it could contribute to the field of solar thermal power plant engineering. The company’s research has focused on using smaller engines and light-weight mirrors with better controlling software — along with a tower outfitted with equipment to receive the concentrated sunlight and run a turbine and generator — to produce electricity. It ran into some technical challenges with engineering a suitable power tower before it decided to shelve the research project.

This power tower design is newer, in terms of deployment, than the parabolic trough technology that uses curved mirrors and fluid-filled tubes to generate steam that run a turbine and generator to produce electricity. The pairing of power towers and the flat mirrors, or heliostats, also can create steam at higher temperatures and are more efficient power plants than the parabolic trough technology.

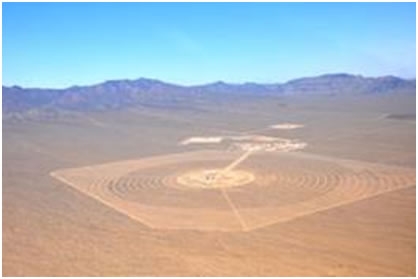

Several companies have been developing power tower designs. BrightSource Energy, for example, is building a 392-megawatt project in California’s Mojave Desert now. Incidentally, Google is an investor in that power plant, though a Google spokesman indicated the company didn’t work with Brightsource on its research project. It did work with Brayton Energy, which is a research and development firm in New Hampshire.

In a blog post Thursday, Google said it wanted to end its solar research effort as part of its RE<C initiative to invest in clean power technology to help it become cost competitive against coal-based energy. The company actually isn’t getting out of clean power investments, which now total more than $850 million, and will continue to put money into buying renewable energy for its data centers and investing in clean power technologies.

Google said it realized that “other institutions are better positioned than Google to take this research to the next level.” Part of this reason could be its renewed focus on projects that have closer ties to its core business. It certainly knew that the problems it was tackling weren’t unheard of, but it was hoping to solve them with perhaps more novel approaches.

A thorny problem that Google engineers faced was the design of the power tower, or the receiver of the concentrated solar energy being beamed by the field of flat mirrors, or heliostats. Google designed the power tower to contain the receiver of the solar energy and the turbine engine that produces the power to run a generator.

The company opted to use the engine that uses the Brayton cycle, which uses the sun’s energy to heat air and run the turbine. A Brayton engine is commonly found in jets and gas turbines, and it heats up compressed air to run the turbine. Google wanted to explore the use of Brayton engine because it doesn’t require water to produce power or for cooling.

The turbines used by BrightSource rely on the Rankine cycle to produce power. Rankine cycle is more commonly used in solar thermal, coal, combined –cycle natural gas and nuclear power plants and typically needs water for producing steam and cooling, a requirement that has raised strong opposition to building solar thermal power plants in arid regions. But arid regions also have been some of the best locations for solar thermal power plants because they receive plenty of sunshine.

Power plant operators can use air for cooling, or condensing the steam back to fluid for re-use. In fact, BrightSource has opted to use air cooling, which is more expensive, in order to minimize criticism of its projects in the American southwest, where the majority of the solar thermal power plant development in the United States is taking place.

Google wanted to design a Brayton engine from scratch instead of modifying existing jet engines, something that it said has been the more common attempt at engineering a system for solar thermal power plants. Brayton engine has a drawback, though. It’s more efficient when it runs more efficiently at high temperatures above 900 degrees Celsius, Google said.

It designed the Brayton engine to be at the top of the tower, along with the receiver that takes in the concentrated sunlight from the mirrors below. The company said designing a proper solar receiver was a tougher challenge than it had anticipated. Apparently there were issues with controlling the temperatures and building a strong receiver structure. The engine won’t run as efficiently if it runs too hot or cold. Google didn’t go into details except to say this: “Temperature gradients were a challenge and metal creep and fatigue were big issues. Available design may be possible with ceramic materials, but much more development is required.”

It did conclude that designing a suitable Brayton engine is perhaps more achievable, and the use of commercially available equipment is possible to reduce costs. Google never built a prototype to test its receiver and engine design, however.

Solar thermal power plant developers such as Abengoa Solar also have been exploring the use of Brayton engines. The ability of a Brayton cycle to run at high temperatures is attractive. Achieving higher temperatures means more efficient conversion of solar energy to electricity, and it’s something that developers of various solar thermal power technologies are aiming.

Parabolic trough plants generally heat up fluid to about 390 degrees Celsius while the power tower designs can achieve around 550 degrees Celsius and higher.

Achieving high temperatures depend largely on the design of the mirrors — how much the optics can concentrate and beam the sunlight to the top of the power tower, said Cliff Ho, a scientist at Sandia National Laboratory, in an interview earlier this year.

Google worked on improving the mirror designs, as well. The project looked at reducing the cost of the glass mirrors and their supporting structures, as well as the software that controls the tilt of the mirrors as they track the sun’s movement. Google said it ran a cost analysis of its work on the heliostat field and believed its research could in fact reduce the equipment and installation costs.

Follow

Follow